http://www.goodui.org/

A Good User Interface has high conversion rates and is easy to use. In other words, it's nice to both the business side as well as the people using it. Here is a running list of practical ideas to try out. You've read all tips. Check back later.

A Good User Interface has high conversion rates and is easy to use. In other words, it's nice to both the business side as well as the people using it. Here is a running list of practical ideas to try out. You've read all tips. Check back later.

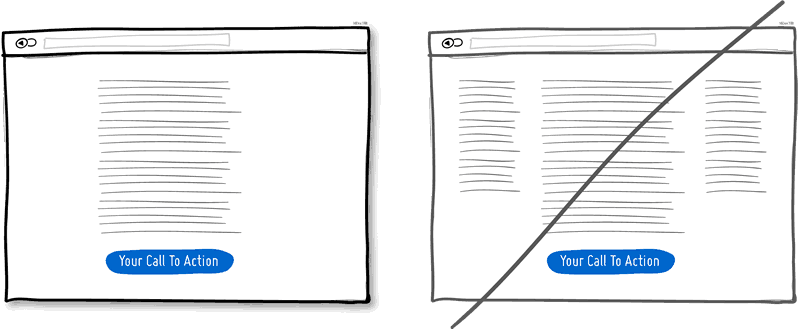

Try A One Column Layout instead of multicolumns.

A one column layout will give you more control over your narrative. It

should be able to guide your readers in a more predictable way from top

to bottom. Whereas a multi column approach runs some additional risk of

being distracting to the core purpose of a page. Guide people with a

story and a prominent call to action at the end.

A one column layout will give you more control over your narrative. It

should be able to guide your readers in a more predictable way from top

to bottom. Whereas a multi column approach runs some additional risk of

being distracting to the core purpose of a page. Guide people with a

story and a prominent call to action at the end.

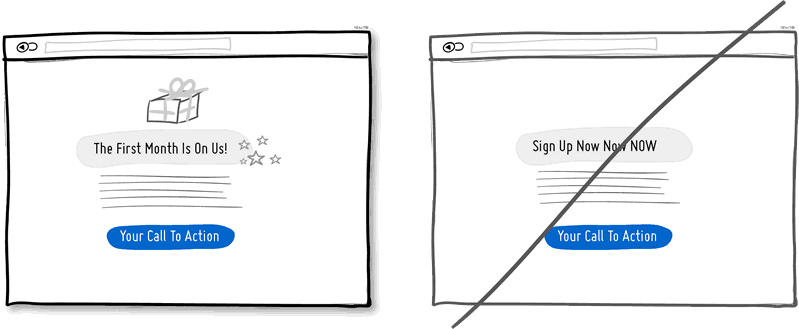

Try Giving a Gift instead of closing a sale right away.

A friendly gesture such as providing a customer with a gift can be just

that. Deeper underneath however, gifting is also an effective persuasion

tactic that is based on the rule of reciprocity. As obvious as it

sounds, being nice to someone by offering a small token of appreciation

can come back in your favour down the road.

A friendly gesture such as providing a customer with a gift can be just

that. Deeper underneath however, gifting is also an effective persuasion

tactic that is based on the rule of reciprocity. As obvious as it

sounds, being nice to someone by offering a small token of appreciation

can come back in your favour down the road.

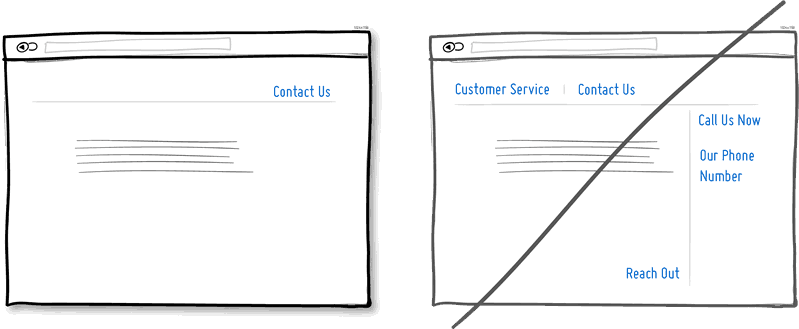

Try Merging Similar Functions instead of fragmenting the UI.

Over the course of time, it's easy to unintentionally create multiple

sections, elements and features which all perform the same function.

It's basic entropy - things start falling apart over time. Keep an eye

out for duplicate functionality labelled in various ways, as it puts a

strain on your customers. Often, the more UI fragmentation there is, the

higher the learning curve which your customers will have to deal with.

Consider refactoring your UI once in a while by merging similar

functions together.

Over the course of time, it's easy to unintentionally create multiple

sections, elements and features which all perform the same function.

It's basic entropy - things start falling apart over time. Keep an eye

out for duplicate functionality labelled in various ways, as it puts a

strain on your customers. Often, the more UI fragmentation there is, the

higher the learning curve which your customers will have to deal with.

Consider refactoring your UI once in a while by merging similar

functions together.

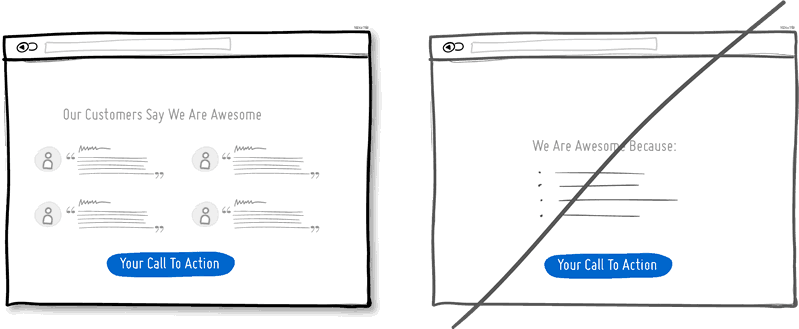

Try Social Proof instead of talking about yourself.

Social proof is another great persuasion tactic directly applicable to

increasing conversion rates. Seeing that others are endorsing you and

talking about your offering, can be a great way to reinforce a call to

action. Try a testimonial or showing data which proves that others are

present.

Social proof is another great persuasion tactic directly applicable to

increasing conversion rates. Seeing that others are endorsing you and

talking about your offering, can be a great way to reinforce a call to

action. Try a testimonial or showing data which proves that others are

present.

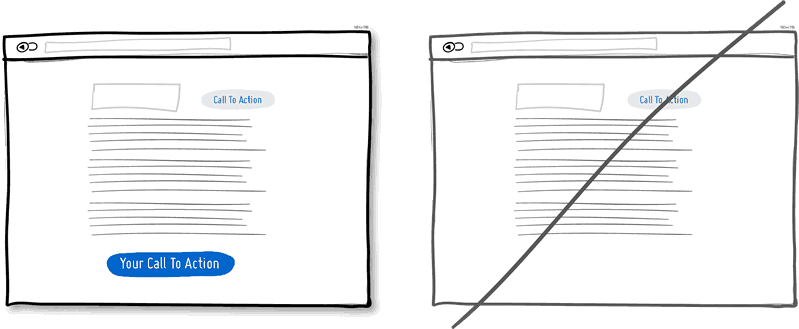

Try Repeating Your Primary Action instead of showing it just once.

Repeating your call to action is a strategy that is more applicable to

longer pages, or repeating across numerous pages. Surely you don't want

to have your offer displayed 10 times all on the same screen and

frustrate people. However, long pages are becoming the norm and the idea

of squeezing everything "above the fold" is fading. It doesn't hurt to

have one soft actionable item at the top, and another prominent one at

the bottom. When people reach the bottom, they pause and think what to

do next - a potential solid place to make an offer or close a deal.

Repeating your call to action is a strategy that is more applicable to

longer pages, or repeating across numerous pages. Surely you don't want

to have your offer displayed 10 times all on the same screen and

frustrate people. However, long pages are becoming the norm and the idea

of squeezing everything "above the fold" is fading. It doesn't hurt to

have one soft actionable item at the top, and another prominent one at

the bottom. When people reach the bottom, they pause and think what to

do next - a potential solid place to make an offer or close a deal.

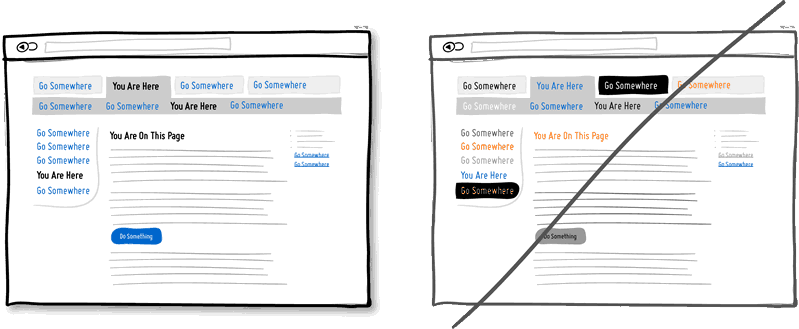

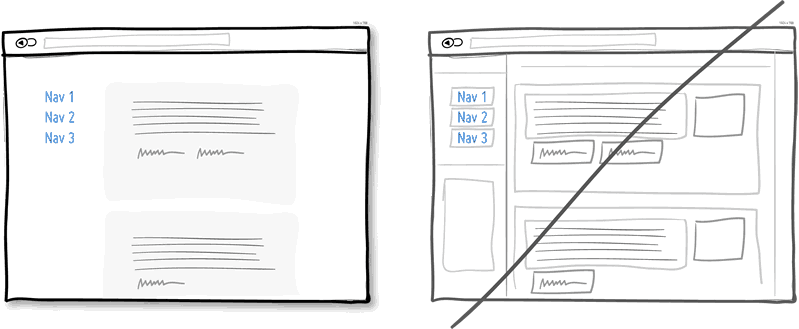

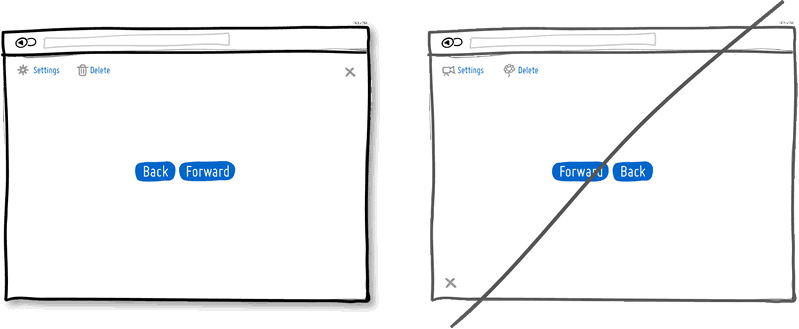

Try Distinct Styles Between Clickable And Selected Items instead of blurring them.

Visual styling such as color, depth, and contrast may be used as a

reliable cue to help people understand the fundamental language of

navigating your interface: where am I, and where can I go. In order to

communicate this clearly to your users, the styles of your clickable

actions (links, buttons), selected elements (chosen items), and plain

text should be clearly distinct from one another and then applied

consistently across an interface. In the visual example, I've chosen a

blue color to suggest anything that can be clicked on, and black as

anything that has been selected or indicates where someone is. When

applied properly, people will more easily learn and use these cues to

navigate your interface. Don't make it harder for people by blurring

these three functional styles.

Visual styling such as color, depth, and contrast may be used as a

reliable cue to help people understand the fundamental language of

navigating your interface: where am I, and where can I go. In order to

communicate this clearly to your users, the styles of your clickable

actions (links, buttons), selected elements (chosen items), and plain

text should be clearly distinct from one another and then applied

consistently across an interface. In the visual example, I've chosen a

blue color to suggest anything that can be clicked on, and black as

anything that has been selected or indicates where someone is. When

applied properly, people will more easily learn and use these cues to

navigate your interface. Don't make it harder for people by blurring

these three functional styles.

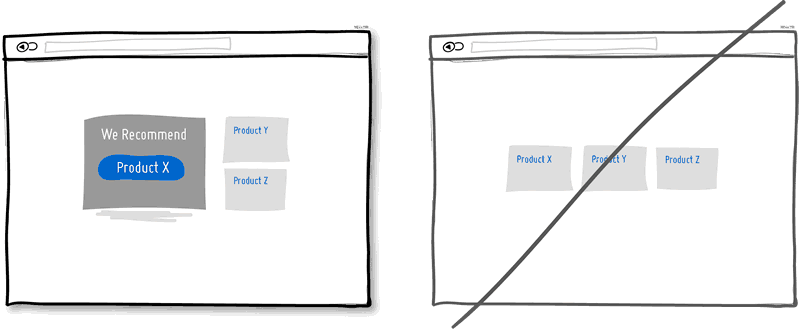

Try Recommending instead of showing equal choices.

When showing multiple offers, then an emphasized product suggestion

might be a good idea as some people need a little nudge. I believe there

are some psychology studies

out there which suggest that the more choice there is, then the lower

the chances of a decision actually being made and acted upon. In order

to combat such analysis paralysis, try emphasizing and highlighting

certain options above others.

When showing multiple offers, then an emphasized product suggestion

might be a good idea as some people need a little nudge. I believe there

are some psychology studies

out there which suggest that the more choice there is, then the lower

the chances of a decision actually being made and acted upon. In order

to combat such analysis paralysis, try emphasizing and highlighting

certain options above others.

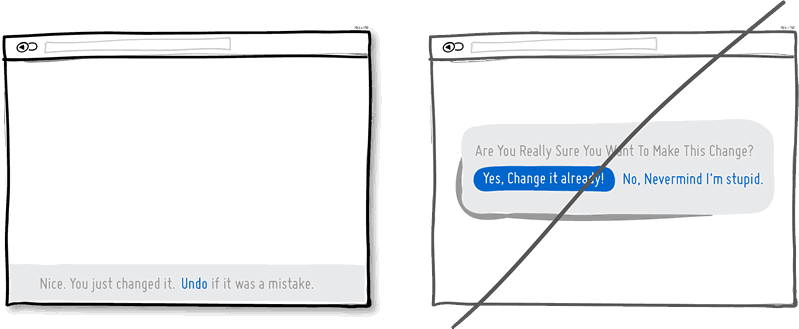

Try Undos instead of prompting for confirmation.

Imagine that you just pressed an action button or link. Undos respect

the initial human intent by allowing the action to happen smoothly first

and foremost. Prompts on the other hand suggest to the user that he or

she does not know what they are doing by questioning their intent at all

times.

I would assume that most of the time human actions are intended and only

in small situations are they accidental. The inefficiency and ugliness

of prompts is visible when users have to perform actions repeatedly and

are prompted numerously over and over - a dehumanizing experience.

Consider making your users feel more in control by enabling the ability

to undo actions and not asking for confirmation where possible.

Imagine that you just pressed an action button or link. Undos respect

the initial human intent by allowing the action to happen smoothly first

and foremost. Prompts on the other hand suggest to the user that he or

she does not know what they are doing by questioning their intent at all

times.

I would assume that most of the time human actions are intended and only

in small situations are they accidental. The inefficiency and ugliness

of prompts is visible when users have to perform actions repeatedly and

are prompted numerously over and over - a dehumanizing experience.

Consider making your users feel more in control by enabling the ability

to undo actions and not asking for confirmation where possible.

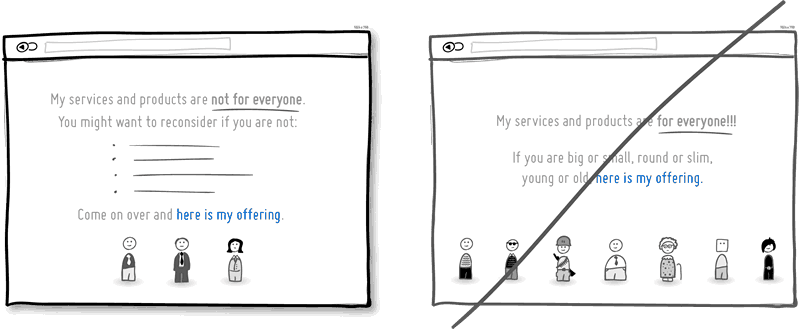

Try Telling Who It's For instead of targeting everyone.

Are you targeting everyone or are you precise with your audience? This

is a conversion idea where you could be explicit about who exactly your

product or service is intended for. By communicating the qualifying

criteria of your customers, you might be able to actually connect more

with them while at the same time hinting at a feeling of exclusivity.

The risk with this strategy of course is that you might be cutting

yourself short and restricting potential customers. Then again,

transparency builds trust.

Are you targeting everyone or are you precise with your audience? This

is a conversion idea where you could be explicit about who exactly your

product or service is intended for. By communicating the qualifying

criteria of your customers, you might be able to actually connect more

with them while at the same time hinting at a feeling of exclusivity.

The risk with this strategy of course is that you might be cutting

yourself short and restricting potential customers. Then again,

transparency builds trust.

(Side note: Enjoying the little characters style? Please be sure to check out MicroPersonas.)

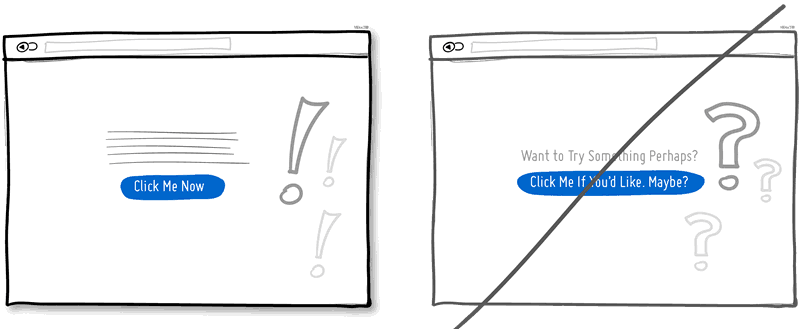

Try Being Direct instead of indecisive.

You can send your message with uncertainty trembling in your voice, or

you can say it with confidence. If you're ending your messaging with

question marks, using terms such as "perhaps", "maybe", "interested?"

and "want to?", then most likely you have some opportunity to be a bit

more authoritative. Who knows, maybe there is a bit more room for

telling people what to do next in the world of conversion optimization.

You can send your message with uncertainty trembling in your voice, or

you can say it with confidence. If you're ending your messaging with

question marks, using terms such as "perhaps", "maybe", "interested?"

and "want to?", then most likely you have some opportunity to be a bit

more authoritative. Who knows, maybe there is a bit more room for

telling people what to do next in the world of conversion optimization.

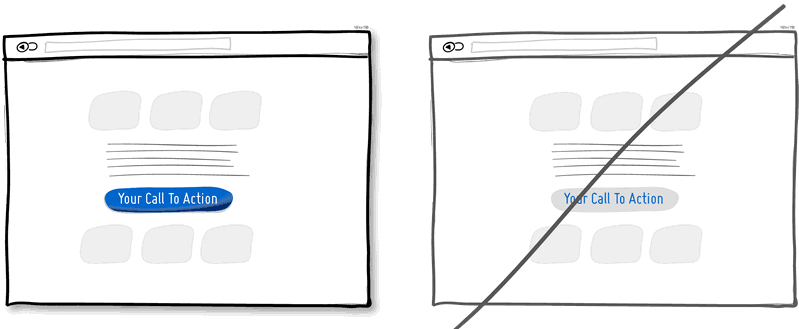

Try More Contrast instead of similarity.

Making your calls to action be a bit more prominent and distinguishable

in relation to the elements surrounding them, will make your UI

stronger. You can easily increase the contrast of your primary calls to

action in a number of ways. Using tone, you can make certain elements

appear darker vs. lighter. With depth, you can make an item appear

closer while the rest of the content looks like it's further (talking

drop shadows and gradients here). Finally, you can also pick

complementary colors from the color wheel (ex: yellow and violet) to

raise contrast even further. Taken together, a higher contrast between

your call to action and the rest of the page should be considered.

Making your calls to action be a bit more prominent and distinguishable

in relation to the elements surrounding them, will make your UI

stronger. You can easily increase the contrast of your primary calls to

action in a number of ways. Using tone, you can make certain elements

appear darker vs. lighter. With depth, you can make an item appear

closer while the rest of the content looks like it's further (talking

drop shadows and gradients here). Finally, you can also pick

complementary colors from the color wheel (ex: yellow and violet) to

raise contrast even further. Taken together, a higher contrast between

your call to action and the rest of the page should be considered.

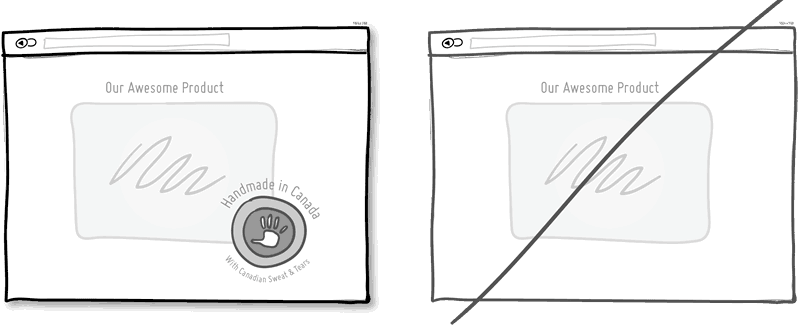

Try Showing Where It's Made instead of being generic.

Indicating where you, your product or service is from says quite a bit

subliminally while at the same time moves your communication to a more

personal level. Mentioning the country, state or city of origin is

surely a very human like way to introduce oneself. If you can do the

same virtually then you just might be perceived as a bit more friendly.

Often, stating where your product is being made at also has a pretty

good chance of making it feel of slightly higher quality. It's a win

win.

Indicating where you, your product or service is from says quite a bit

subliminally while at the same time moves your communication to a more

personal level. Mentioning the country, state or city of origin is

surely a very human like way to introduce oneself. If you can do the

same virtually then you just might be perceived as a bit more friendly.

Often, stating where your product is being made at also has a pretty

good chance of making it feel of slightly higher quality. It's a win

win.

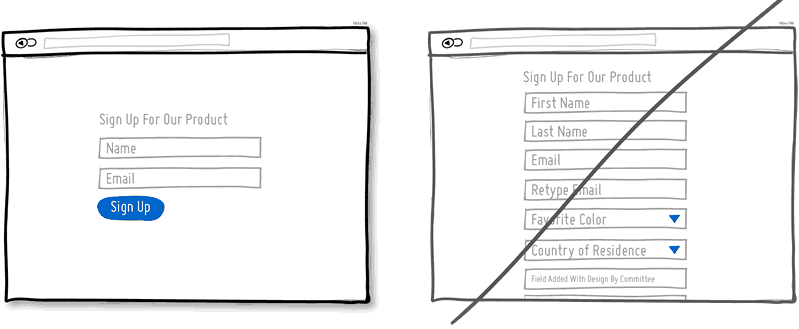

Try Fewer Form Fields instead of asking for too many.

Human beings are inherently resistant to labor intensive tasks and this

same idea also applies to filling out form fields. Each field you ask

for runs the risk of making your visitors turn around and give up. Not

everyone types at the same speed, while typing on mobile devices is

still a chore in general. Question if each field is really necessary and

remove as many fields as possible. If you really have numerous optional

fields, then also consider moving them after form submission on a

separate page or state. It's so easy to bloat up your forms, yet fewer

fields will convert better.

Human beings are inherently resistant to labor intensive tasks and this

same idea also applies to filling out form fields. Each field you ask

for runs the risk of making your visitors turn around and give up. Not

everyone types at the same speed, while typing on mobile devices is

still a chore in general. Question if each field is really necessary and

remove as many fields as possible. If you really have numerous optional

fields, then also consider moving them after form submission on a

separate page or state. It's so easy to bloat up your forms, yet fewer

fields will convert better.

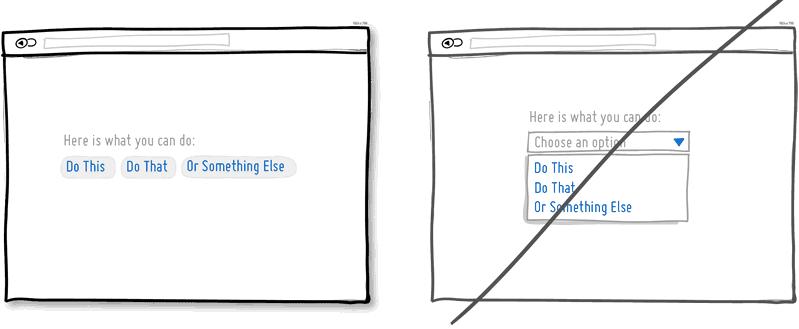

Try Exposing Options instead of hiding them.

Each pull down menu that you use, hides a set of actions within which

require effort to be discovered. If those hidden options are central

along the path to getting things done by your visitors, then you might

wish to consider surfacing them a bit more up front. Try to reserve pull

down menus for options that are predictable and don’t require new

learning as in sets of date and time references (ex: calendars) or

geographic sets. Occasionally pull down menu items can also work for

those interfaces that are highly recurring in terms of use - actions

that a person will use repeatedly over time (ex: action menus). Be

careful of using drop downs for primary items that are on your path to

conversion.

Each pull down menu that you use, hides a set of actions within which

require effort to be discovered. If those hidden options are central

along the path to getting things done by your visitors, then you might

wish to consider surfacing them a bit more up front. Try to reserve pull

down menus for options that are predictable and don’t require new

learning as in sets of date and time references (ex: calendars) or

geographic sets. Occasionally pull down menu items can also work for

those interfaces that are highly recurring in terms of use - actions

that a person will use repeatedly over time (ex: action menus). Be

careful of using drop downs for primary items that are on your path to

conversion.

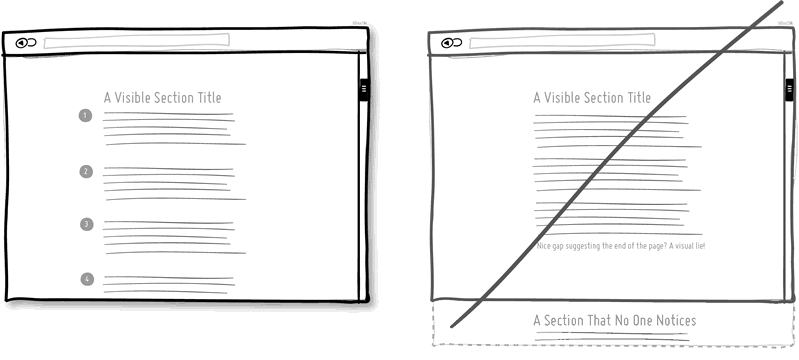

Try Suggesting Continuity instead of false bottoms.

A false bottom is a conversion killer. Yes, scrolling long pages are

great, but be careful of giving your visitors a sense that the page has

come to an end somewhere in between sections where it really hasn't. If

your pages will scroll, try to establish a visual pattern or rhythm that

the user can learn and rely on to read further down. Secondarily, be

careful of big gaps in around the areas of where the fold can appear (of

course I’m referring to a area range here with so many device sizes out

there).

A false bottom is a conversion killer. Yes, scrolling long pages are

great, but be careful of giving your visitors a sense that the page has

come to an end somewhere in between sections where it really hasn't. If

your pages will scroll, try to establish a visual pattern or rhythm that

the user can learn and rely on to read further down. Secondarily, be

careful of big gaps in around the areas of where the fold can appear (of

course I’m referring to a area range here with so many device sizes out

there).

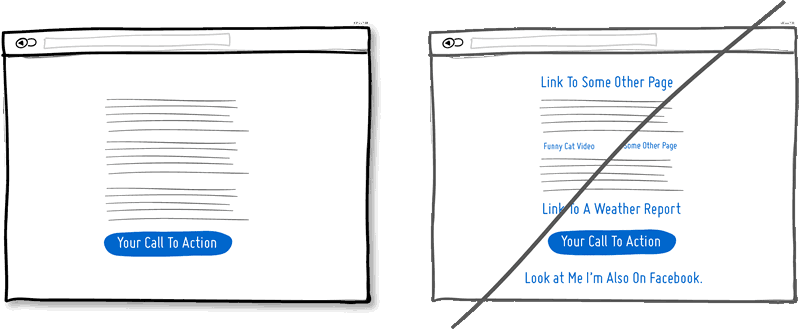

Try Keeping Focus instead of drowning with links.

It’s easy to create a page with lots of links going left and right in

the hope of meeting as many customer needs as possible. If however

you’re creating a narrative page which is building on towards a specific

call to action at the bottom, then think twice. Be aware that any link

above the primary CTA runs the risk of taking your customers away from

what you’ve been hoping them to do. Keep an eye out on the number of

links on your pages and possibly balance discovery style pages (a bit

heavier on the links) with tunnel style pages (with fewer links and

higher conversions). Removing extraneous links can be a sure way to

increase someone’s chances of reaching that important button.

It’s easy to create a page with lots of links going left and right in

the hope of meeting as many customer needs as possible. If however

you’re creating a narrative page which is building on towards a specific

call to action at the bottom, then think twice. Be aware that any link

above the primary CTA runs the risk of taking your customers away from

what you’ve been hoping them to do. Keep an eye out on the number of

links on your pages and possibly balance discovery style pages (a bit

heavier on the links) with tunnel style pages (with fewer links and

higher conversions). Removing extraneous links can be a sure way to

increase someone’s chances of reaching that important button.

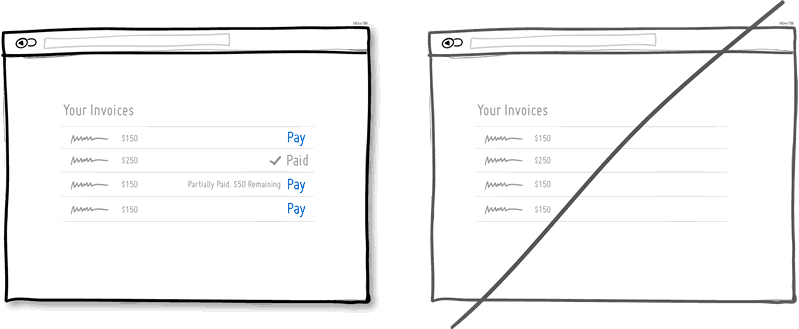

Try Showing State instead of being state agnostic.

In any user interface we quite often show elements which can have

different states. Emails can be read or unread, invoices can be paid or

not, etc. Informing users about the particular state in which an item is

in, is a good way of providing feedback. Interface states can help

people understand whether or not their past actions have been

successfully carried out, as well as whether an action should be taken.

In any user interface we quite often show elements which can have

different states. Emails can be read or unread, invoices can be paid or

not, etc. Informing users about the particular state in which an item is

in, is a good way of providing feedback. Interface states can help

people understand whether or not their past actions have been

successfully carried out, as well as whether an action should be taken.

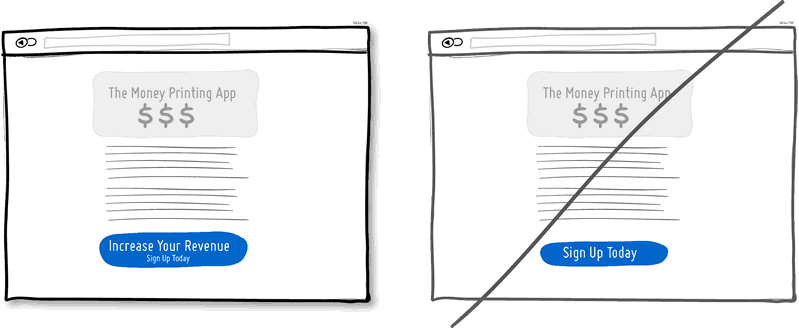

Try Benefit Buttons instead of just task based ones.

Imagine two simple buttons displayed on a page. One button tells you

that it will “Save You Money”, while the other one asks you to “Sign

Up”. I’d place my bets that the first one might have a higher chance of

being acted on, as a sign up on it’s own has no inherent value. Instead,

a sign up process takes effort and is often associated with lengthy

forms of some sort. The hypothesis set here is that buttons which

reinforce a benefit might lead to higher conversions. Alternatively, the

benefit can also be placed closely to where the action button is in

order to remind people why they are about to take that action. Surely,

there is still room for task based actions buttons, but those can be

reserved for interface areas that require less convincing and are more

recurring in use.

Imagine two simple buttons displayed on a page. One button tells you

that it will “Save You Money”, while the other one asks you to “Sign

Up”. I’d place my bets that the first one might have a higher chance of

being acted on, as a sign up on it’s own has no inherent value. Instead,

a sign up process takes effort and is often associated with lengthy

forms of some sort. The hypothesis set here is that buttons which

reinforce a benefit might lead to higher conversions. Alternatively, the

benefit can also be placed closely to where the action button is in

order to remind people why they are about to take that action. Surely,

there is still room for task based actions buttons, but those can be

reserved for interface areas that require less convincing and are more

recurring in use.

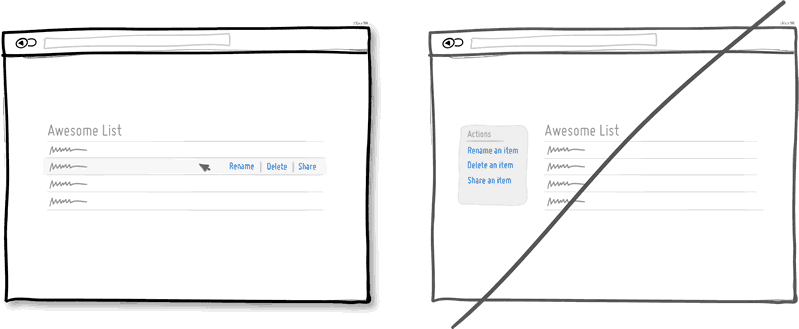

Try Direct Manipulation instead of contextless menus.

Occasionally it makes sense to allow certain UI elements to be acted

upon directly as opposed to listing unassociated generic actions. When

displaying lists of data for example, we typically want to allow the

user to do something with the items in the list. Clicking on, or

hovering over an item in this list can be used to express that a

particular item is to be manipulated (deleted, renamed, etc.). Another

example of common direct manipulation would be clicking on a data item

(say a text based address) which then turns into an editable field.

Enabling such interactions cuts through the number of required steps,

compared to if the same task was started more generally without the

context of the item - since selection is already taken care of. Do keep

in mind of course that for generic item-agnostic actions, there is

nothing wrong with contextless menus.

Occasionally it makes sense to allow certain UI elements to be acted

upon directly as opposed to listing unassociated generic actions. When

displaying lists of data for example, we typically want to allow the

user to do something with the items in the list. Clicking on, or

hovering over an item in this list can be used to express that a

particular item is to be manipulated (deleted, renamed, etc.). Another

example of common direct manipulation would be clicking on a data item

(say a text based address) which then turns into an editable field.

Enabling such interactions cuts through the number of required steps,

compared to if the same task was started more generally without the

context of the item - since selection is already taken care of. Do keep

in mind of course that for generic item-agnostic actions, there is

nothing wrong with contextless menus.

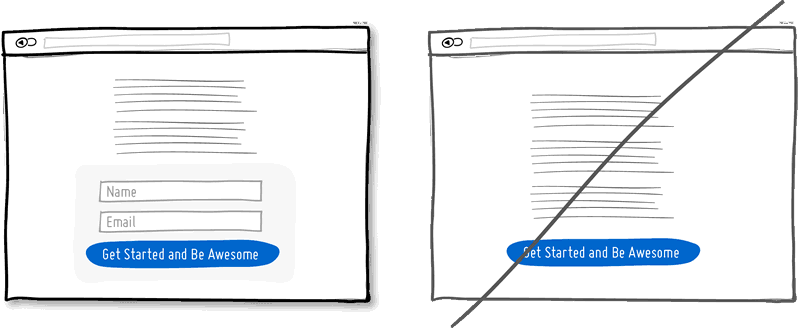

Try Exposing Fields instead of creating extra pages.

When creating landing pages that convey value, it can be beneficial to

show the actual form fields on the conversion page itself. Merging the

sign up form with the landing page comes with a number of benefits in

comparison to creating separate multi-page sign ups. First, we are

cutting out extra steps from the flow in general and the task at hand

takes less time. Secondly, by showing the number of form fields right

there, we are also providing the customer with a sense of how long the

sign up actually is. This of course is a little easier when our forms

are shorter in the first place (which of course they should be if

possible).

When creating landing pages that convey value, it can be beneficial to

show the actual form fields on the conversion page itself. Merging the

sign up form with the landing page comes with a number of benefits in

comparison to creating separate multi-page sign ups. First, we are

cutting out extra steps from the flow in general and the task at hand

takes less time. Secondly, by showing the number of form fields right

there, we are also providing the customer with a sense of how long the

sign up actually is. This of course is a little easier when our forms

are shorter in the first place (which of course they should be if

possible).

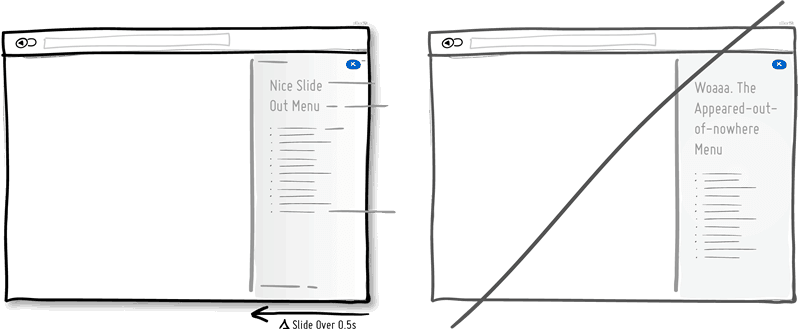

Try Transitions instead of showing changes instantly.

Interface elements often appear, hide, move, shift, and resize as users

do their thing. As elements respond to our interactions, it sometimes is

a little easier to comprehend what just happened when we sprinkle in

the element of time. A built in intentional delay in the form of an

animation or transition, respects cognition and gives people the

required time to understand a change in size or position. Keep in mind

of course that as we start increasing the duration of such transitions

beyond 0.5 seconds, there will be situations where people might start

feeling the pain. For those who just wish to get things done quickly,

too long of a delay of course can be a burden.

Interface elements often appear, hide, move, shift, and resize as users

do their thing. As elements respond to our interactions, it sometimes is

a little easier to comprehend what just happened when we sprinkle in

the element of time. A built in intentional delay in the form of an

animation or transition, respects cognition and gives people the

required time to understand a change in size or position. Keep in mind

of course that as we start increasing the duration of such transitions

beyond 0.5 seconds, there will be situations where people might start

feeling the pain. For those who just wish to get things done quickly,

too long of a delay of course can be a burden.

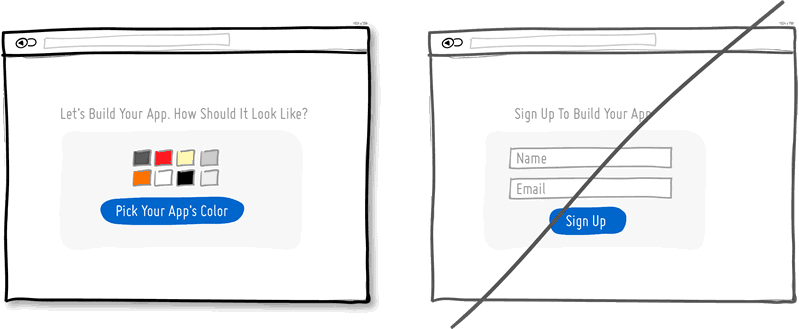

Try Gradual Engagement instead of a hasty sign up.

Instead of asking visitors to sign up immediately, why not ask them to

first perform a task through which something of value is demonstrated.

During such initial interactions the product can both show off its

benefits, as well as can lend itself to personalization. Once users

begin to see your product’s value and see how they can make it their

own, they will then be more open to sharing with you additional

information. Gradual engagement is really a way to postpone the sign up

process as much as possible and still allow users to use and customize

your application or product.

Instead of asking visitors to sign up immediately, why not ask them to

first perform a task through which something of value is demonstrated.

During such initial interactions the product can both show off its

benefits, as well as can lend itself to personalization. Once users

begin to see your product’s value and see how they can make it their

own, they will then be more open to sharing with you additional

information. Gradual engagement is really a way to postpone the sign up

process as much as possible and still allow users to use and customize

your application or product.

Try Fewer Borders instead of wasting attention.

Borders compete for attention with real content. Attention of course is a

precious resource since we can only grasp so much at any given time.

Surely borders can be used to define a space very clearly and precisely,

but they also do cost us cognitive energy as they are perceived as

explicit lines. In order to define relationships between screen elements

which use less attention, elements can also be just grouped together

through proximity, be aligned, have distinct backgrounds, or even just

share a similar typographic style. When working in abstract UI tools,

it’s easy to drop a bunch of boxes everywhere. Boxes however come with a

false sense of being immune from the order and unity which governs the

rest of the screen. Hence pages with lots of boxes sometimes may tend to

look noisy or misaligned. Sometimes it is helpful to throw in a line

here and there, but do consider alternative ways of defining visual

relationships that are less taxing to attention and your content will

come through.

Borders compete for attention with real content. Attention of course is a

precious resource since we can only grasp so much at any given time.

Surely borders can be used to define a space very clearly and precisely,

but they also do cost us cognitive energy as they are perceived as

explicit lines. In order to define relationships between screen elements

which use less attention, elements can also be just grouped together

through proximity, be aligned, have distinct backgrounds, or even just

share a similar typographic style. When working in abstract UI tools,

it’s easy to drop a bunch of boxes everywhere. Boxes however come with a

false sense of being immune from the order and unity which governs the

rest of the screen. Hence pages with lots of boxes sometimes may tend to

look noisy or misaligned. Sometimes it is helpful to throw in a line

here and there, but do consider alternative ways of defining visual

relationships that are less taxing to attention and your content will

come through.

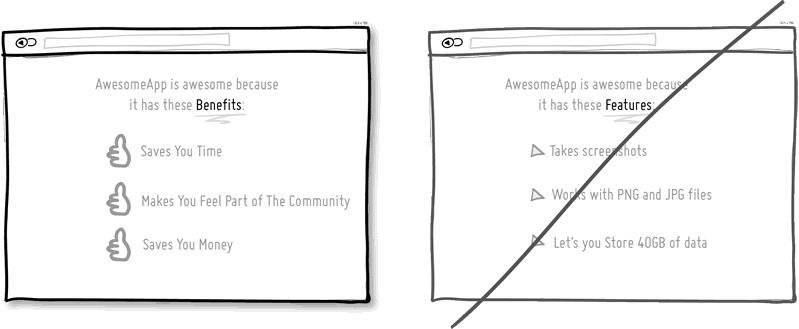

Try Selling Benefits instead of features.

I think this is Marketing 101. People tend to care less about features

than they do about benefits. Benefits carry with them more clearly

defined value. Chris Guillebeau in "The $100 Startup" writes that people

really care about having more of: Love, Money, Acceptance and Free

Time, while at the same time wishing for less Stress, Conflict, Hassle

and Uncertainty. When showing features, and I do believe that there is

still room for them occasionally, be sure to tie them back to benefits

where possible.

I think this is Marketing 101. People tend to care less about features

than they do about benefits. Benefits carry with them more clearly

defined value. Chris Guillebeau in "The $100 Startup" writes that people

really care about having more of: Love, Money, Acceptance and Free

Time, while at the same time wishing for less Stress, Conflict, Hassle

and Uncertainty. When showing features, and I do believe that there is

still room for them occasionally, be sure to tie them back to benefits

where possible.

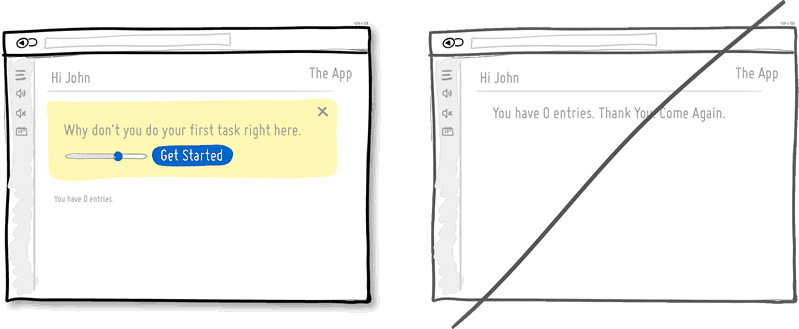

Try Designing For Zero Data instead of just data heavy cases.

There are cases when you will have 0, 1, 10, 100, or 10,000+ data

results which might need to be displayed somehow in various ways. The

most common of these scenarios is probably the transition from first

time use with zero data towards future use with a lot more data. We

often forget to design for this initial case when there is still nothing

to display whatsoever, and by doing so we run the risk of neglecting

users. A zero data world is a cold place. When first time users look at

your app and all it does is show a blank slate without any guidance then

you’re probably missing out on an opportunity. Zero data states are

perfect candidates for getting users across the initial hurdle of

learning by showing them what to do next. Good things scale and user

interfaces are no exception.

There are cases when you will have 0, 1, 10, 100, or 10,000+ data

results which might need to be displayed somehow in various ways. The

most common of these scenarios is probably the transition from first

time use with zero data towards future use with a lot more data. We

often forget to design for this initial case when there is still nothing

to display whatsoever, and by doing so we run the risk of neglecting

users. A zero data world is a cold place. When first time users look at

your app and all it does is show a blank slate without any guidance then

you’re probably missing out on an opportunity. Zero data states are

perfect candidates for getting users across the initial hurdle of

learning by showing them what to do next. Good things scale and user

interfaces are no exception.

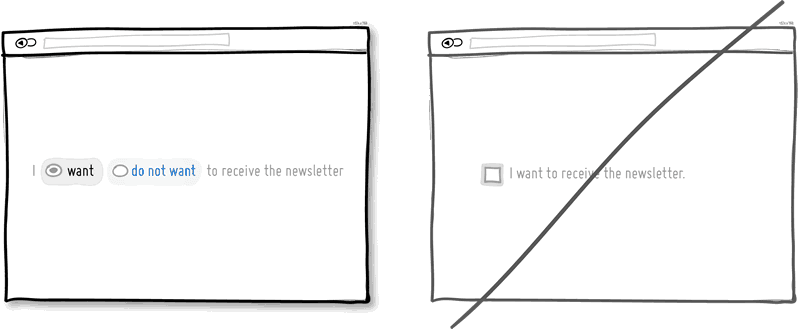

Try Opt-Out instead of opt-in.

An opt-out strategy implies that users or customers are defaulted to

take part in something without having to take any action. Alternatively,

there is also the more traditional opt-in strategy that requires people

to first take an action in order to take part in or receive something.

There are two good reasons why opt-out works better than opt-in. First

it alleviates resistance on the path of action, as the user does not

have to do anything. Secondly, it’s also a form of recommendation which

implies some kind of a norm - “since everyone else takes this as it is, I

might also do the same”.

Of course the opt-out strategy is often perceived as controversial as

there are those sleazy marketers which will abuse it. One such evil is

to diminish the readability of the opt-out text, while another is to use

confusing text, such as double negatives. Both examples will result in

users being less aware of actually signing up for something.

Hence to keep the ethics in check, if you do decide to go with an

opt-out approach, do make it very clear and understandable to your

customers what they are being defaulted into. After all, this tactic has

also been used in Europe to save lives.

An opt-out strategy implies that users or customers are defaulted to

take part in something without having to take any action. Alternatively,

there is also the more traditional opt-in strategy that requires people

to first take an action in order to take part in or receive something.

There are two good reasons why opt-out works better than opt-in. First

it alleviates resistance on the path of action, as the user does not

have to do anything. Secondly, it’s also a form of recommendation which

implies some kind of a norm - “since everyone else takes this as it is, I

might also do the same”.

Of course the opt-out strategy is often perceived as controversial as

there are those sleazy marketers which will abuse it. One such evil is

to diminish the readability of the opt-out text, while another is to use

confusing text, such as double negatives. Both examples will result in

users being less aware of actually signing up for something.

Hence to keep the ethics in check, if you do decide to go with an

opt-out approach, do make it very clear and understandable to your

customers what they are being defaulted into. After all, this tactic has

also been used in Europe to save lives.

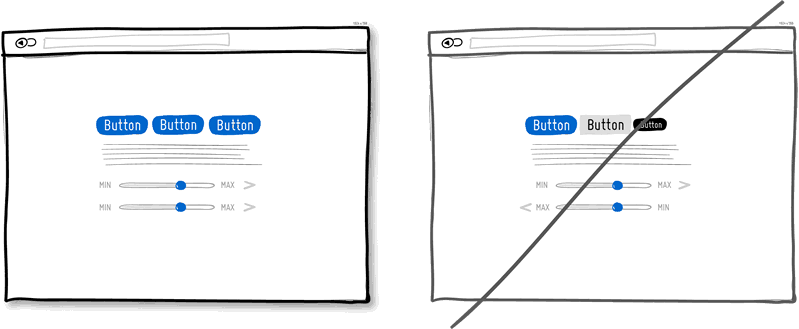

Try Consistency instead of making people relearn.

Striving for consistency in user interface design is probably one of the

most well known principles since Donald Norman’s awesome books. Having a

more consistent UI or interaction is simply a great way to decrease the

amount of learning someone has to go through as they use an interface

or product. As we press buttons and shift sliders, we learn to expect

these interaction elements to look, behave and be found in the same way

repeatedly. Consistency solidifies the way we learn to interact and as

soon as it is taken away, we are then forced back into learning mode all

over again. Consistent interfaces can be achieved through a wide

possible range of things such as: colors, directions, behaviors,

positioning, size, shape, labelling and language.

Before we make everything consistent however, please let’s bear in mind

that keeping things inconsistent still has value. Inconsistent elements

or behaviors come out into attention from the depths of our habitual

subconscious - which can be a good thing when you want to have things

get noticed. Try it, but know when to break it.

Striving for consistency in user interface design is probably one of the

most well known principles since Donald Norman’s awesome books. Having a

more consistent UI or interaction is simply a great way to decrease the

amount of learning someone has to go through as they use an interface

or product. As we press buttons and shift sliders, we learn to expect

these interaction elements to look, behave and be found in the same way

repeatedly. Consistency solidifies the way we learn to interact and as

soon as it is taken away, we are then forced back into learning mode all

over again. Consistent interfaces can be achieved through a wide

possible range of things such as: colors, directions, behaviors,

positioning, size, shape, labelling and language.

Before we make everything consistent however, please let’s bear in mind

that keeping things inconsistent still has value. Inconsistent elements

or behaviors come out into attention from the depths of our habitual

subconscious - which can be a good thing when you want to have things

get noticed. Try it, but know when to break it.

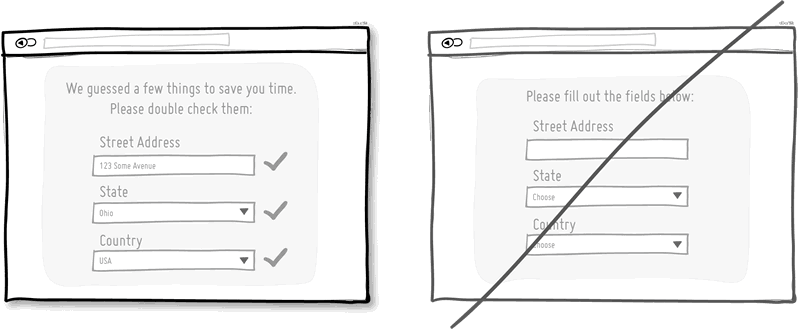

Try Smart Defaults instead of asking to do extra work.

Using smart defaults or pre-filling form fields with educated guesses

removes the amount of work users have to do. This is a common technique

for helping users move through forms faster by being respectful of their

limited time. One of the worst things from an experience and conversion

stand point is to ask people for data that they have already provided

in the past, repeatedly over and over again. Try to display fields that

are preloaded with values to be validated as opposed to asking for

values to be retyped each time. The less work, the better.

Using smart defaults or pre-filling form fields with educated guesses

removes the amount of work users have to do. This is a common technique

for helping users move through forms faster by being respectful of their

limited time. One of the worst things from an experience and conversion

stand point is to ask people for data that they have already provided

in the past, repeatedly over and over again. Try to display fields that

are preloaded with values to be validated as opposed to asking for

values to be retyped each time. The less work, the better.

Try Conventions instead of reinventing the wheel.

Convention is the big brother of consistency. If we keep things similar

across an interface, people won’t have to obviously struggle as hard. If

on the other hand, we all keep things as similar as possible across

multiple interfaces, that decreases the learning curve even further.

With the help of established UI conventions we learn to close screen

windows in the upper right hand corner (more often than not), or expect a

certain look from our settings icons. Of course there will be times

when a convention no longer serves purpose and gives way to a newer

pattern. When breaking away, do make sure it’s purposefully thought out

and with good intention.

Convention is the big brother of consistency. If we keep things similar

across an interface, people won’t have to obviously struggle as hard. If

on the other hand, we all keep things as similar as possible across

multiple interfaces, that decreases the learning curve even further.

With the help of established UI conventions we learn to close screen

windows in the upper right hand corner (more often than not), or expect a

certain look from our settings icons. Of course there will be times

when a convention no longer serves purpose and gives way to a newer

pattern. When breaking away, do make sure it’s purposefully thought out

and with good intention.

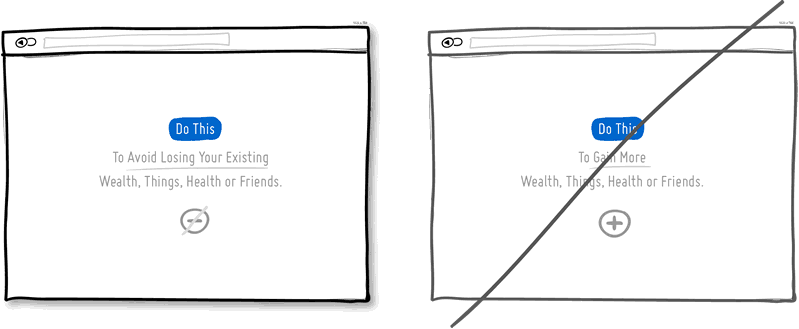

Try Loss Aversion instead of emphasizing gains.

We like to win, but we hate to lose. According to the rules of persuasive psychology,

we are more likely to prefer avoiding losses than to acquiring gains.

This can be applied to how product offerings are framed and

communicated. By underlying that a product is protective of a customer’s

existing well-being, wealth or social status, such strategy might be

more effective than trying to provide a customer with something

additional which they don’t already have. Do insurance companies sell

the payout that can be gained after the accident or the protection of

the things we hold dear to us?

We like to win, but we hate to lose. According to the rules of persuasive psychology,

we are more likely to prefer avoiding losses than to acquiring gains.

This can be applied to how product offerings are framed and

communicated. By underlying that a product is protective of a customer’s

existing well-being, wealth or social status, such strategy might be

more effective than trying to provide a customer with something

additional which they don’t already have. Do insurance companies sell

the payout that can be gained after the accident or the protection of

the things we hold dear to us?

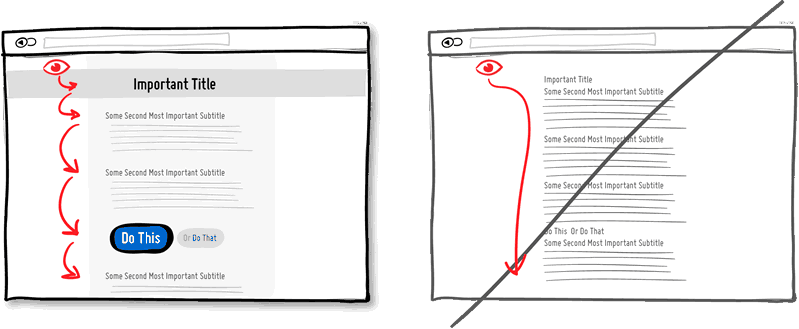

Try Visual Hierarchy instead of dullness.

A good visual hierarchy can be used to separate out your important

elements from the less important ones. A visual hierarchy results from

varying such things as alignment, proximity, colour, tone, indentation,

font size, element size, padding, spacing, etc. When these visual

language elements are applied correctly, they can work together to

direct and pause people’s attention within a page - improving general

readability.

A visual hierarchy can be said to generate friction and slows us down

from skimming through the full page top to bottom - for the better that

is. With a good visual hierarchy, although we might spend a bit more

time on the page, the end result should be that we register more items

and characteristics. Think of it as as road trip. You can take the

highway and get to your destination quicker (bottom of page), or you can

take the scenic route and remember more interesting things along the

way. Give the eye a place to stop.

A good visual hierarchy can be used to separate out your important

elements from the less important ones. A visual hierarchy results from

varying such things as alignment, proximity, colour, tone, indentation,

font size, element size, padding, spacing, etc. When these visual

language elements are applied correctly, they can work together to

direct and pause people’s attention within a page - improving general

readability.

A visual hierarchy can be said to generate friction and slows us down

from skimming through the full page top to bottom - for the better that

is. With a good visual hierarchy, although we might spend a bit more

time on the page, the end result should be that we register more items

and characteristics. Think of it as as road trip. You can take the

highway and get to your destination quicker (bottom of page), or you can

take the scenic route and remember more interesting things along the

way. Give the eye a place to stop.

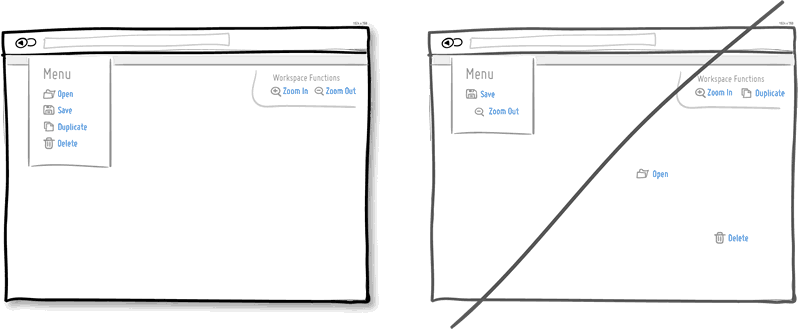

Try Grouping Related Items instead of disordering.

Grouping related items together is a basic way of increasing fundamental

usability. Most of us tend to know that a knife and a fork, or open and

save functions can typically be found more or less together. Related

items are just meant to be placed in proximity of each other in order to

respect a degree of logic and lower overall cognitive friction. Wasting

time looking for stuff usually isn't fun for people.

Grouping related items together is a basic way of increasing fundamental

usability. Most of us tend to know that a knife and a fork, or open and

save functions can typically be found more or less together. Related

items are just meant to be placed in proximity of each other in order to

respect a degree of logic and lower overall cognitive friction. Wasting

time looking for stuff usually isn't fun for people.

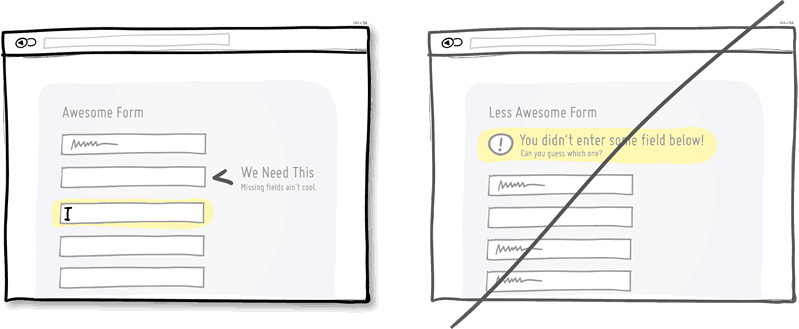

Try Inline Validation instead of delaying errors.

When dealing with forms and errors, it’s usually better to try to detect

if something isn’t correct and show it sooner rather than later. The

famous interaction pattern highlighted here of course is inline

validation. By showing an error message as it happens (say to the right

of the input field), it can be corrected right then and there as it

appears in context. On the other hand, when error messages are displayed

later on (say after a submit), it forces people to do some additional

cognitive work of having to recall what they were doing from a few steps

back.

When dealing with forms and errors, it’s usually better to try to detect

if something isn’t correct and show it sooner rather than later. The

famous interaction pattern highlighted here of course is inline

validation. By showing an error message as it happens (say to the right

of the input field), it can be corrected right then and there as it

appears in context. On the other hand, when error messages are displayed

later on (say after a submit), it forces people to do some additional

cognitive work of having to recall what they were doing from a few steps

back.

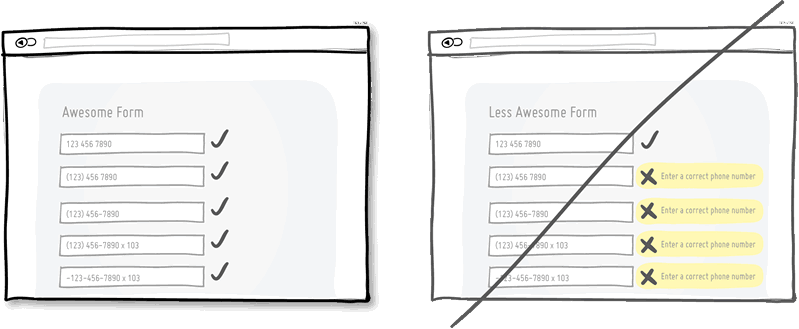

Try Forgiving Inputs instead of being strict with data.

Being more forgiving in terms of user entered data, computers can move

one step closer towards becoming a bit more humane. Forgiving inputs

anticipates and understands a variety of data formats and thereby makes

your UI more friendly. A perfect example of this is when we ask people

for a phone number which can be entered in so many different ways - with

brackets, extensions, dashes, area codes, and on. Have your code work a

bit harder so that your users won’t have to.

Being more forgiving in terms of user entered data, computers can move

one step closer towards becoming a bit more humane. Forgiving inputs

anticipates and understands a variety of data formats and thereby makes

your UI more friendly. A perfect example of this is when we ask people

for a phone number which can be entered in so many different ways - with

brackets, extensions, dashes, area codes, and on. Have your code work a

bit harder so that your users won’t have to.

More On The Way. Sign Up Below For The Newsletter.